With the rapid development of wearable electronic devices, fiber-based intelligent electronic textiles have demonstrated enormous application prospects in areas including health monitoring, smart display, and human-computer interaction. However, how to effectively retain and transfer the intrinsic properties of high-performance nanomaterials to macroscopic fiber structures has long been a key challenge. Especially for two-dimensional materials such as MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ), which possess exceptional mechanical strength and electrical conductivity, their nanosheets tend to form numerous voids during the assembly into macroscopic fibers due to transverse wrinkling and weak interlayer interfacial interactions. This severely impairs the mechanical and electrical properties of the resultant fibers, thus limiting their applications in durable, high-performance smart textiles.

Recently, a research team led by Professor Wei Lei from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, and Professor Cheng Qunfeng from the University of Science and Technology of China, has proposed a controllable static-dynamic densification strategy, successfully enabling the continuous fabrication of kilometer-scale ultra-strong MXene composite fibers. This method employs short carbon nanotubes (CNTs) for static filling and combines it with dynamic thermal stretching of polylactic acid (PLA). By bridging MXene nanosheets via hydrogen bonds, the internal voids of the fibers are significantly reduced. The resulting composite fibers achieve a tensile strength of up to 941.5 MPa, an electrical conductivity of 3899.0 S cm⁻¹ (with the internal MXene fibers exhibiting an even higher conductivity of 12,836.4 S cm⁻¹), a porosity as low as 4.2%, and a nanosheet orientation factor of up to 0.945.

Smart textiles embroidered with such fibers enable long-distance, battery-free wireless health monitoring, somatosensory remote control of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and auxiliary communication, while also demonstrating excellent mechanical durability. This strategy provides a universal pathway for preparing high-performance fibers based on various nanoscale functional materials. The relevant research paper, entitled "Ultrastrong MXene composite fibers through static-dynamic densification for wireless electronic textiles", has been published in Nature Communications.

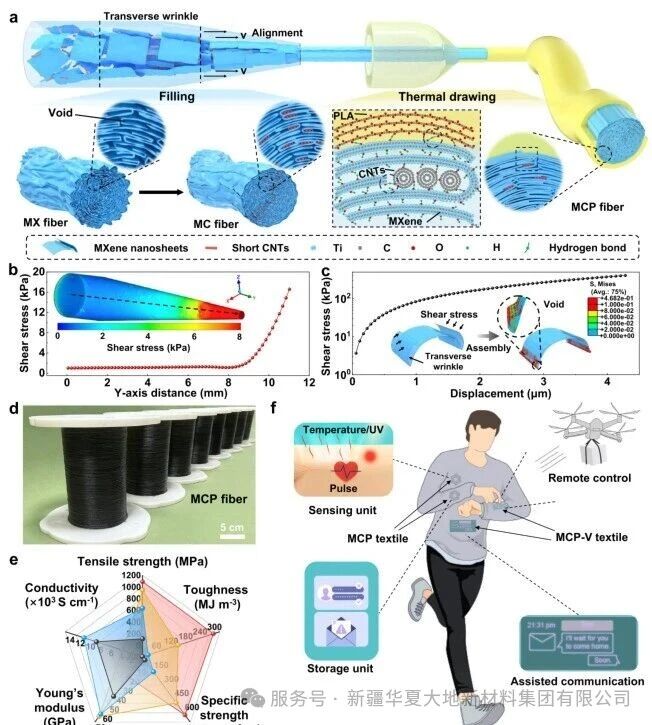

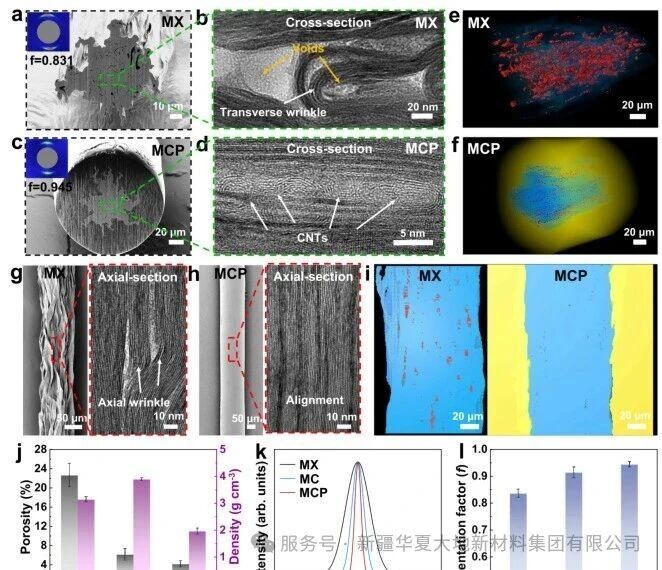

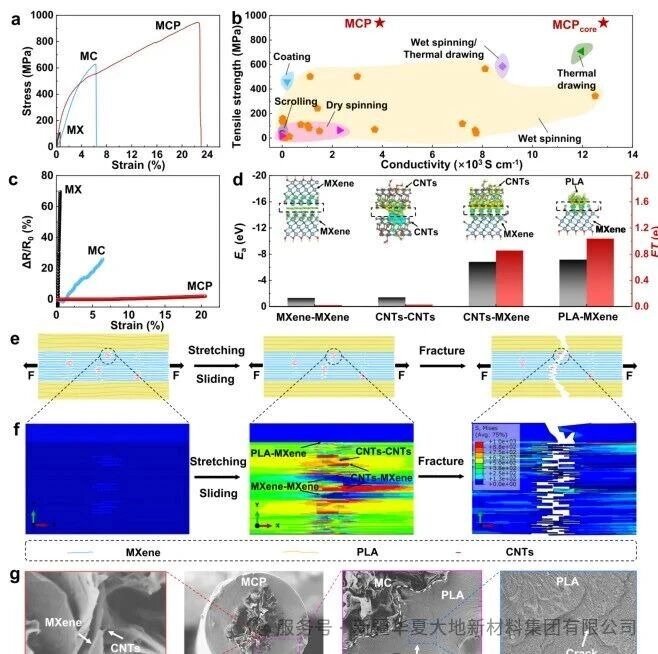

First, the research team revealed the fundamental reason why MXene nanosheets generate transverse wrinkles and form voids due to insufficient shear force during the wet-spinning process by means of atomic force microscopy and finite element analysis (Figure 1). To address this issue, they innovatively introduced short carboxylated carbon nanotubes as "fillers". These one-dimensional CNTs can effectively bridge MXene nanosheets via hydrogen bonds, statically fill the voids caused by wrinkles during the spinning process, and preliminarily improve the compactness and orientation of MXene-CNTs (MC) composite fibers (Figures 1a, 2a-d). Subsequently, they adopted a dynamic thermal stretching process, feeding the MC fibers into polylactic acid (PLA) preforms for stretching. The dynamic stress generated by thermal stretching further compresses the residual voids, and simultaneously forms an in-situ PLA coating layer on the exterior of the fibers. This layer is also bonded to the internal MXene nanosheets via hydrogen bonds, ultimately yielding MCP composite fibers with a highly dense structure and excellent oriented arrangement (Figures 1d, 2c, f). The fibers can reach a kilometer-scale length and bear a weight of 1.5 kilograms (Figure 1d).

First, the research team revealed the fundamental reason why MXene nanosheets generate transverse wrinkles and form voids due to insufficient shear force during the wet-spinning process by means of atomic force microscopy and finite element analysis (Figure 1). To address this issue, they innovatively introduced short carboxylated carbon nanotubes as "fillers". These one-dimensional CNTs can effectively bridge MXene nanosheets via hydrogen bonds, statically fill the voids caused by wrinkles during the spinning process, and preliminarily improve the compactness and orientation of MXene-CNTs (MC) composite fibers (Figures 1a, 2a-d). Subsequently, they adopted a dynamic thermal stretching process, feeding the MC fibers into polylactic acid (PLA) preforms for stretching. The dynamic stress generated by thermal stretching further compresses the residual voids, and simultaneously forms an in-situ PLA coating layer on the exterior of the fibers. This layer is also bonded to the internal MXene nanosheets via hydrogen bonds, ultimately yielding MCP composite fibers with a highly dense structure and excellent oriented arrangement (Figures 1d, 2c, f). The fibers can reach a kilometer-scale length and bear a weight of 1.5 kilograms (Figure 1d).

Through Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy analyses, the researchers confirmed the successful formation of hydrogen bonds between CNTs-MXene and PLA-MXene (see relevant analyses in Figure 2). Three-dimensional reconstructed images from nano-computed tomography clearly show that pure MXene fibers contain a large number of voids (marked in red), whereas MCP fibers exhibit significantly reduced voids and a much denser structure (Figures 2e, f). In addition, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy images of the axial cross-sections demonstrate that after static filling and dynamic stretching, the MXene nanosheets inside the fibers are highly ordered in arrangement, with wrinkles largely eliminated (Figures 2g–i). The study also systematically optimized the length and dosage of CNTs, revealing that the filling effect and performance improvement are most pronounced when the CNT length is ~0.46 μm and the dosage is 3 wt% (Figures 2j–l).

Benefiting from the dense structure and strong interfacial hydrogen bonding interactions, the MCP fibers achieved breakthrough mechanical and electrical properties (Figure 3a). Their tensile strength and toughness reached 9 times and 411 times those of pure MXene fibers, respectively. Compared with all previously reported MXene-based fibers, the MCP fibers take a leading position in terms of both strength and electrical conductivity (Figure 3b). Real-time resistance-strain tests showed that the resistance of MCP fibers changed minimally (~2%) before fracture, indicating that their internal structure remained intact during deformation (Figure 3c). Cyclic loading tests also verified that the MCP fibers retained 85.6% of their electrical conductivity after 4000 cycles, with durability far superior to that of the control samples. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations and finite element simulations revealed the fracture mechanism: during stretching, the MXene-MXene interfaces with relatively weak bonding strength slipped first; subsequently, the stronger hydrogen bonds between CNTs-MXene and PLA-MXene fractured sequentially and dissipated energy; the pull-out of CNTs and the cracking of the PLA coating layer further contributed to the high toughness and high strength of the fibers (Figures 3d–g).

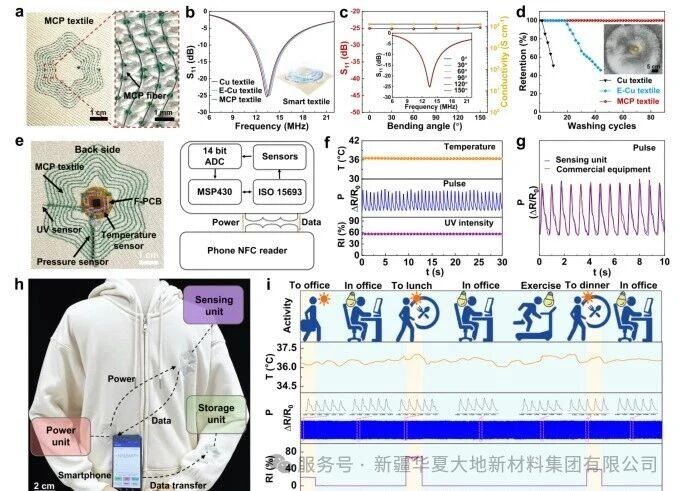

By integrating such ultra-strong and highly conductive MCP fibers into fabrics via digital embroidery technology, high-performance wireless smart textiles can be fabricated (Figure 4a). Taking the flower-shaped spiral inductor pattern as an example, the electromagnetic performance (S₁₁ parameter) of MCP textiles is comparable to that of commercial copper wire textiles, while demonstrating overwhelming advantages in mechanical durability (Figure 4b). After undergoing 90,000 cycles of 180° bending, 30,000 cycles of 360° torsion, 50,000 cycles of stretching under 20% strain, and 90 cycles of standard washing, the MCP textiles retained over 99% of their electrical conductivity, whereas the comparative copper wire textiles fractured long before (Figures 4c, d). This is mainly attributed to the inherent high strength, high toughness, and dense structure of MCP fibers.

Based on this, the research team developed a long-distance, battery-free wireless health monitoring system (Figures 4e–i). The system consists of spiral inductors embroidered on a hoodie (serving as wireless power supply and communication antennas), sensing units integrated with temperature, pulse, and ultraviolet intensity sensors, as well as a data storage unit worn on the wrist. Users only need to bring a smartphone close to the garment to activate the system, enabling wireless collection, transmission, and storage of physiological data over a distance of more than 50 cm, and achieving stable monitoring of different daily activities for up to 12 hours (Figure 4i).

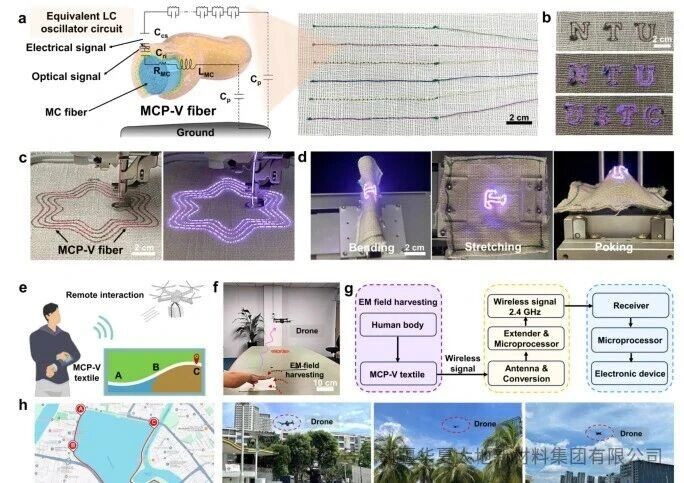

Furthermore, the research team prepared MCP-V fibers with a three-layer structure by coating the outer layer of MCP fibers with vinyl silicone resin/acetate silicone resin and ZnS:Cu²⁺ phosphors (Figure 5a). While maintaining high mechanical properties, these fibers also possess the ability to emit light and generate wireless signals under in-vivo coupled electromagnetic fields, and can operate without batteries. When embroidered into patterns or characters, they can be made into luminescent textiles for auxiliary communication (Figures 5b, c), with stable luminescence even under deformations such as bending and stretching (Figure 5d). More importantly, using such fiber fabrics, wireless signal transmission triggered by human touch can be realized, thereby remotely controlling unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to complete a series of complex operations including take-off, landing, forward movement and load-bearing, with a control distance of up to approximately 5 kilometers (Figures 5e–h).

This work presents a densification strategy combining static filling and dynamic thermal stretching, which successfully addresses the issues of wrinkling and void formation during MXene nanosheet assembly, and fabricates composite fibers with integrated ultrahigh mechanical performance, high electrical conductivity and excellent durability. The smart textiles developed therefrom exhibit great application potential in wireless health monitoring and remote somatosensory interaction. This versatile strategy paves a new way for preparing high-performance fibers using various nanostructured functional materials and advancing the development of next-generation wearable electronic devices.